|

Artwork by Tema Okun

The late

Kenneth Jackson Jones (1950-2004) was a visionary and a leader, an organizer and a teacher, a friend and a colleague. Kenneth was instrumental in developing the dismantling racism curriculum and process at ChangeWork and carried on by the dRworks collaborative after his untimely death. Kenneth's positive impact on the lives of so many of us is a reflection of his enormous contribution to our continued commitment to realize a just world. |

I - Tema Okun - wrote the original article on White Supremacy Culture in 1999. At the time I had been working closely for over half a decade with my mentor, teacher, and colleague Kenneth Jones. When I originally published it, I listed him as co-author because so much of the wisdom in the piece was a result of our collaborative work together. When he realized I had named him as a co-author, he demanded that I take his name off the piece, claiming he didn't want credit for something he didn't actually write. We argued and, given his seniority and determination, he won the argument, although many versions of the original article are still circulating with both our names on it. I am totally thrilled about that because his wisdom has informed any that I might have.

At the time, in addition to working closely with Kenneth, I was living in the Bay area. As a result, I had the privilege of attending The Challenging White Supremacy Workshop series organized by my mentor Sharon Martinas as well as a People's Institute for Survival and Beyond workshop (one of many as I would attend as often as I could). The original article, and by extension the characteristics as described on this website, were heavily influenced by my experiences the year I lived in the Bay. These included extensive facilitation and training work on the West coast throughout that year with Kenneth. I also showed the very first draft to Sharon, who counseled that I could not list the characteristics without offering antidotes, so the suggestions for how to show up to each other in ways that support our mutual thriving are a result of this wise advice. I was also informed by the teaching of Daniel Buford, who was one of the lead trainers with the People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond at the workshop I attended. He was doing extensive research on white supremacy culture and linguistic racism and you will see the portions that he asked to be credited for both on the original article and here marked by an asterisk. The original piece also built on the work of many other people as well. These are people whose work informed the curriculum and training that Kenneth and I were leading at the time as well as colleagues in the work with us. These brilliant people include (but not limited to) Andrea Ayvazian, Bree Carlson, Beverly Daniel Tatum, Eli Dueker, Nancy Emond, Jonn Lunsford, Joan Olsson, David Rogers, James Williams, Sally Yee, as well as the work of Grassroots Leadership, Equity Institute Inc, the People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond, the Challenging White Supremacy workshop, the Lillie Allen Institute, the Western States Center, and the contributions of hundreds of participants in the DR process. I will also say that the original article was my one and only experience of producing something that came through me (see the Characteristics page for the whole story). The original article, this website, and the work I continue to do is in honor and memory of Kenneth, who helped me become wise about many things and kept me honest about everything else. I love him and miss him beyond words. His laugh, his caring, his wisdom are with me always. |

|

A lot of time has passed since the original article on White Supremacy Culture was published. While the article seems to be getting a lot of use in this time of resurgent anti-racist movement building, it does need to be revised and updated. For example, I (and colleagues) have come to see other central elements of white supremacy culture that need to be named: fear is an essential characteristic, as is the assumption of "qualified" attached to whiteness. Defensiveness needs to be broadened to include denial, which is included in the list in this current iteration. A class lens and issues of intersectionality are important to address.

The original list is really a list of white supremacy characteristics that define and express white middle and owning class values and norms. White middle- and owning-class power brokers embody these characteristics as a way of defining what is "normal" and even "aspirational" or desired – the way we should all want to be. We know this because of how those who do not belong to the white middle and owning classes are required to adopt these characteristics in order to assimilate into this desired norm (when such assimilation is allowed). As a result, many poor and working class white people report they have not and do not internalize some of these norms. For example, fear of open conflict does not reflect the lived experience or value of all people in the white group. These characteristics are not meant to describe all white people. They are meant to describe the norms of white middle-class and owning class culture, a culture we are all required to navigate regardless of our multiple identities. I also want to acknowledge that none of these characteristics stand alone; they intersect and intertwine in devastating ways. I have combined some that act as best buddies: one right way and perfectionism, for example, and right to comfort with fear of open conflict. One of the ways that white supremacy gets us is how we internalize these characteristics into our very personalities. So, for example, people often ask me, when I am facilitating a class or workshop - isn't the perfectionism you just admitted to simply part of your personality? "Isn't that just who you are?" they ask. My response is "yes it is." My personality is deeply informed by my embodiment as an upper class cisgender white woman. White supremacy culture would have us believe that we can (and should) pinpoint our motivations or actions to determine if they are based on our racism (those of us who are white) or some other aspect of our personality. The idea seems to be that if we "prove" our perfectionism isn't motivated by racism, then it's "all right," when in fact, our perfectionism is never all right. Thank goodness our commitment to our own growth and development as anti-racist white people allows us to see the ways in which our internalizations of superiority warp our relationships not just with BIPOC people and communities, but with other white people and with ourselves. This is the magic of racial justice work. Our commitment to racial justice is a healing practice for all aspects of our lives. Finally, I also hope that adding storytelling, poetry, art, and links to the wisdom of others offers broader ways of knowing and learning and growing. My goal is to offer examples of how these characteristics play out and their cost on a personal, cultural, and institutional level. The desire is to communicate the power of antidotes to create connection and belonging. |

and... dRworks cofounder and trainer and longtime beloved friend Michelle Johnson hosts the Finding Refuge podcast, which emerged from her work based in the exploration of collective grief and liberation. The podcast reminds us about all the ways we can find refuge during unsettling and uncertain times, and about the resilience and joy that comes from allowing ourselves to find refuge. In this fourth episode, Michelle has a conversation with me about Love and Humility. and ... In this edition of the podcast White People Make Everything About Race, I offer my latest thinking on the (mis)use of this article and website and other thoughts about white supremacy culture - including some evolution of my understanding over the past few years. |

I am still trying to answer this question. In the meantime, here's some of what I know.

My name is Tema Okun. I have been on this planet for many decades and I know a thing or two about a thing or two, including white supremacy and racism. And, as you might guess, there are hundreds, thousands, an infinite number of things I don't know and still wonder about. I was born into an upper middle-class family, my father the son of first generation Jewish immigrants escaping the pogroms in Belarus and my mother the daughter of a postal clerk father and housewife mother, both with immigrant roots in Scotland or Ireland. She grew up in a very small town in Texas. By the time I was born, my father was a college professor in an elite Southern college town and my mother worked on and off in the public schools. I grew up during the last years of Jim Crow and the first years of school desegregation, both enactments of violent white supremacy and racism. My parents were liberals in the best sense of that word and very active in the local Civil Rights Movement. I was well cared for materially; emotionally the grounding was less solid and that's a longer story for another day. I am a white woman, currently cisgender and able-bodied, upper class. I am older, sometimes an elder. I have lots of so-called credentials - degrees and a book and articles and poetry and art and curriculum and talks and speeches and teaching and consulting and mentoring and ... my hope is you would care more about my heart than anything. I am conditioned to be fearful while determined to be open-hearted and I live in that ongoing tension each day with as much grace and humor as I can muster. I am deeply puzzled by why and how we seem to value profit over people and why and how we base our belonging on who we can keep out rather than who we welcome in. And by we, I mean our culture, our white supremacy capitalist patriarchal ableist heteronormative fool of a culture. I am deeply moved by how so many of us do all in our power to refuse the invitation into such toxicity and I admire both up close and from afar all engaged in the solidarity effort to live into the world we all want and deserve. I am lucky beyond words to be well loved by a community of people, which is why I have any kind of open heart at all. I aspire to remember every day that I love you as I love myself, and we all know, or most of us do, what a struggle it can be to love ourselves well. Learning to love well is my current project. Thank you, thank you for all you are and do. |

AND GRATITUDE FOR ...

|

some people

|

|

We had come to make peace, Kenneth and me.

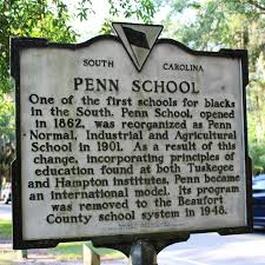

Kenneth, living comfortably in his dark black skin with his easy, self-assured demeanor and me, a self-conscious white woman in my late thirties. A couple of years my senior, Kenneth radiated a confidence that offered a kind of joy or perhaps it was the other way around. He assumed I would offer the same, not knowing, for how could he, that I was neither certain nor ebullient. My focused sentiment, at least in that moment, was worry. I was worried about my ability to pull off what I had been charged to do, which was to work with this man in a version of ceasefire between our two organizations, each engaged in the hostilities of turf and power. Kenneth was agent for a Yankee organization funding the southern communities where the people in my North Carolina based organization lived and worked. We resented their paternalism, one we perhaps projected, and felt resentful about their limited knowing of our first-hand experience. They begrudged our resentment. All of us knew the dangers of such simmering. Hopes for a truce rested with the two of us as we headed into two days of training and teaching. The plan was to meet on hallowed ground deep in the heart of the South Carolina Sea Islands. The Penn Center was both ragged and holy. Over a century and a half ago, in 1862, the Penn School offered classes to formerly enslaved people, opening with 80 students and growing to over 600 before financial defeat during the Great Depression. By the time of this story, it was a struggling retreat center. Whitewashed buildings set under giant oaks draping their silver moss boas sat scattered across the small compound, most sagging with age and memories. As we approached in our small car, dropping from the blacktop of the road to the dirt of the driveway into the property, our conversation dropped too, the history of this place commanding silent respect. Our respective organizations had invited 30 social justice activists to join us at this sacred site; Kenneth and I were the “experts” charged with supporting their desire to build strong community-based organizations. Kenneth was there to teach about long range planning and board development; I would teach about fundraising. Kenneth and I waited and watched as Black and Brown and a few white bodies of all shapes and sizes arrived and filled the metal folding chairs set in a circle inside the pale beige walls of the worn out meeting hall. Voices and laughter boomeranged across the space as people recognized old friends and made new ones. The activists gathered together that weekend were for the most part young and they released a palpable and infectious eagerness. Kenneth offered his welcome and introductions. The crowd responded with their focused attention as he moved into a style of instruction that was part stand-up comedy, part precise and engrossing lecture. He encouraged cross talk and familiarity as he dispensed his particular wisdom about the urgency of sound leadership and thoughtful planning. He moved in and out of the circle, calling on first this person and then the next in a scattershot dance of give and take and always, always laughter. He dug deeper into the specifics, making his case, pushing his points. People shouted out questions and sometimes he answered and more often turned the question back to the group. His love and regard for the people gathered in this circle grounded him; his mastery appeared both smooth and easy. I sat and I watched, mesmerized, transfixed. Although I was no match for Kenneth, witnessing his teaching inspired me. What I planned to share about fundraising had come to me through many hours of being taught by the best. Doing what I was taught to do brought money. So I planned to share my experience and success. Though self-conscious, I knew myself a strong teacher. What I had grasped about teaching was half intuitive and half paying attention to what had worked for me. The daughter of a college professor father and an English teacher mother, I nonetheless struggled in traditional classrooms. A decade and a half of public school followed by four years of dreaded college simply confirmed my inability to fit into systems that packaged intelligence in boxes I could not open. At the time of this gathering, I was just beginning to catch on to my own intelligence. Deeply introverted, also shy, I found refuge in the performance of teaching. So when my turn came, I rose from my chair and began. I told stories and my own version of jokes, drew charts on the flip chart paper. I organized the circle of people into pairs and small groups to talk and laugh and learn together. I buzzed my own energy, flew my own words, laughed my own laughter into the room. And then Tatia rose to her feet. Tatia was young, Black, a woman as sure and confident and fierce as any you can imagine. She stood, her short solid body brightly clothed, her face determined under a crown of tight braids. She launched her accusation in a voice strong and clear – “This is some bullshit. This will not work in our communities. Everything you’re teaching is for white people. This is a complete waste of our time.” Her words echoed from the ceiling; her recrimination hung in the silence. I stood utterly still. Time stopped in the way it does whenever anyone breaches the etiquette of forced civility to speak a truth out loud. I sucked in my breath and held it until the fear rising from my belly forced it out again. Another young African-American woman among the group, Karimah, told me years later what happened next, for I myself have no memory of it. Apparently I blurted out - “Well, if you don’t want to learn about what works, that's your problem” – before walking quickly and surely out of the room. That I said these words is unimaginable to me. To say such a thing is not in any way who I was then – a people pleaser, a conflict avoider, afraid too often of my own shadow, not to mention my own power. What I remember thinking as I fled the room was that I had just blown this peacemaking, trust building mission that I had been assigned. Surely Kenneth, witness to this scene, would walk away from the disaster that I now represented. This thought left me flushing with humiliation – for being called out so publicly and for being nailed with such truth. My chest filled with furious fear. Sighting a chair, I threw myself down onto it and began to sob. I cradled my head in my hands, breath heaving, moans and tears fighting for advantage. I look back over the arc of many decades to this sobbing white woman with a mix of both compassion and irritation. For this is what I know now. Tatia was right. I had little business teaching about fundraising to people living in communities whose financial and racial histories were so different from mine, particularly because I was not prepared to acknowledge the limits along with the usefulness of what I had to offer. This ignorance of my own limits is the legacy of our white supremacy culture where those of us who are white are led to believe that we are the norm from which everyone else can and should learn. I think about how I never stopped to consider, in preparing for this peacemaking task, that my knowledge and experience might not be a solid match for the knowledge and experience and questions of the people I was preparing to teach. How I never stopped to consider the limits of what I knew. How I never stopped to consider what wisdom this group of people might bring about their communities' long histories of raising money to support and care for each other in the face of virulent and violent racism. How I never stopped to consider my responsibility to bridge the racial divide in a room where I would be one of only a few other white people. How I never stopped to consider presenting myself truthfully, with some content knowledge that we, together as a group, could consider for its usefulness and its limits in an open and transparent way. How I never stopped to consider, in that moment of challenge, to simply breathe and say “tell me more.” Instead, I cradled my head and sobbed, with a fervor that dwindled finally to a more quiet sniffle. Minutes passed and I turned silent, aware that Kenneth had followed me and was standing close, patiently waiting. Reluctantly, my rather ordinary face, now bloated, flushed red, and dotted with tears looked up to face him. His dark eyes returned a kind gaze and he said, quite simply, “the problem here, Tema, is you just need to trust your material.” With this short sentence, Kenneth saw beyond my defensiveness and white lady tears into who I had the promise of becoming. He showed me a different way than the one I chose with Tatia. Instead of a defensive protection of his own ego that might want nothing more than to distance itself from such self pity, Kenneth offered a faith in me that I had rarely experienced in my three decades of living. By the end of the training weekend, four or five members of the group put on a skit mimicking both Kenneth and me with an exaggerated and extremely accurate performance of our mannerisms and style. Whatever my transgressions, at least some in the room had, like Kenneth, forgiven my inability to respond to Tatia’s challenge with more open-heartedness. Years later, Tatia and I would laugh about this story, the anger and humiliation dissipated by years and the forgiveness that sometimes comes with growing older. This story marked the beginning of an arc of grace. This was the moment I began to explore the possibility of meeting others and myself where we actually are instead of worrying so much about any performance of knowing or expertise. I saw through Kenneth's eyes that what I knew, what we all know, has some usefulness and could, with open-heartedness, lead to shared learning across lived experience. I recognized how, with a short and very sweet expression of faith in me, Kenneth transformed my fear of failure into over a decade of mutual support and collaboration. I know now, without any doubt, that Kenneth's capacity to see my humanity beyond my conditioned whiteness was a gift of straightforward grace that indeed saved my life. |

|

|

White Supremacy Culture | Offered by Tema Okun

first published 2021 | last update 8.2023 |