|

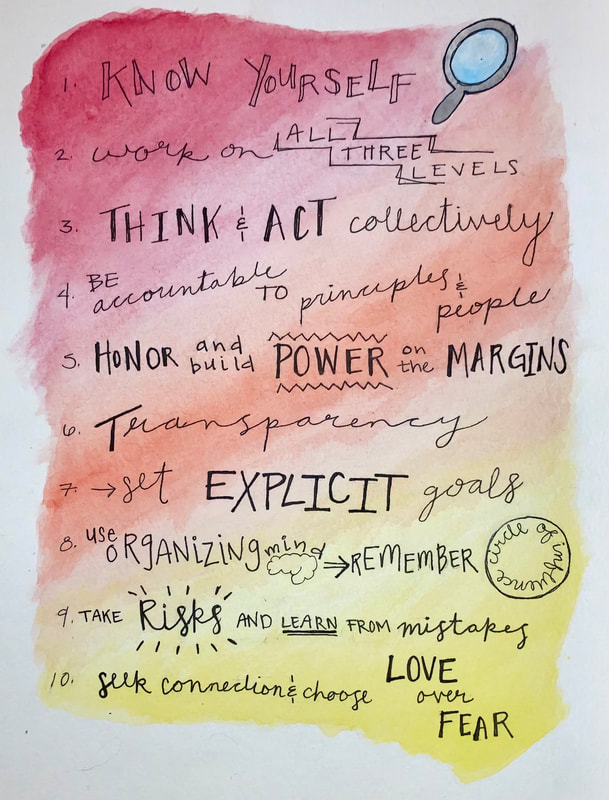

These racial equity principles were developed by the Dismantling Racism Works collaborative after a decade of experience working with and for community based leaders and organizations living into their racial justice commitment. Over our years of working together, members of the collaborative have added to the principles based on our evolving understanding of what we need in order to support racial justice work. We have found these principles to ground us powerfully in the wisdom they offer as we navigate the challenges, constraints, and violations of white supremacy culture. As we build the world we want and deserve. As we become free.

|

There is no liberation without practice.

Lama Rod Owens Love and Rage |

Artwork by Katherine Valde

|

These principles are based in three assumptions.

The first is that we need to understand and respect and generate power. Transformative healing power. Grounded power. Power to create our own realities in ways that respect our interdependence with each other and the earth and the water and spirit and all living beings. We are so accustomed to witnessing people abuse power - for profit mostly or for the ability to wield power. And white supremacy capitalism has so twisted hearts and bodies and minds that we often abuse power and each other in a desperate attempt to feel in control of something, anything. We must become even more bold about our right to be righteously and rightfully powerful - in our own hearts, minds, and bodies and then collectively as we shape and become our governors, our government. We must demand that we use power well and thoughtfully in service of each and all of us. The second assumption is, like the characteristics themselves, these principles are interconnected and informed by context. Knowing ourselves helps us to think and act collectively as we use organizing mind to build connection and accountability. The third assumption is that these principles do not apply universally for everyone in every situation. Understanding our power in any given context will inform us how to use the principles. They do offer a way in, a way through, a grounding of sorts. I use at least two or three of them every day. Please, as with everything, take what is useful and adapt or leave the rest. |

know yourself |

|

Artwork by Leahjo Carnine

If we don't do our work, then we become work for other people. Lama Rod Owens

Love and Rage For more on this, take a look at Adrienne Marie Brown's book We Will Not Cancel Us.

Also listen to this wonderful podcast episode offered by Langston Kahn about Liberating Our Imagination to free ourselves from the harmful stories and energetic patterning of white supremacy and settler-colonialism we carry within us. |

Taking action for racial justice requires a level of self-awareness that supports us to be clear about what we are called to do, what we know how to do, and where we need to grow. Said another way, we need to know our strengths, our weaknesses, and our desire for growth. Knowing ourselves means that we develop the capacity to show up more appropriately and effectively to whatever the work is, that we ask for help when needed, admit when we don’t know what we’re doing and claim our skills gracefully when we do. Knowing ourselves mean that we are committed to our own emotional maturity and wisdom.

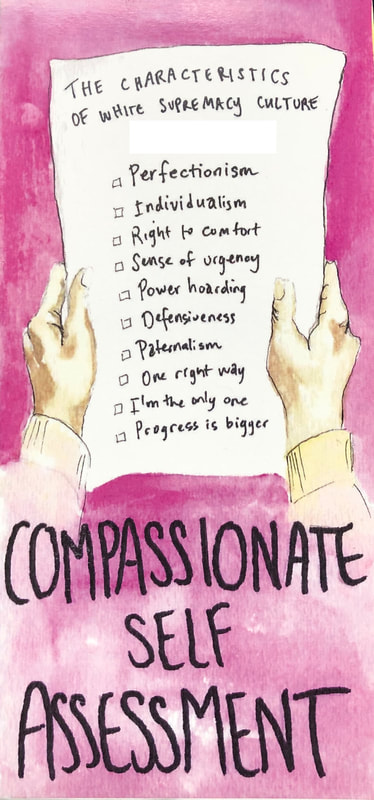

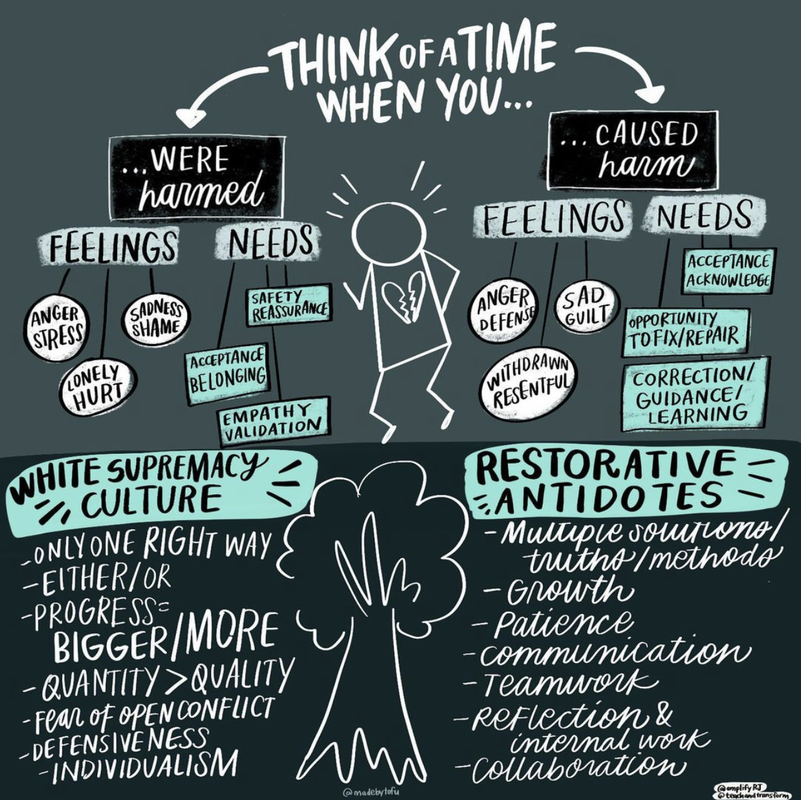

Knowing ourselves means admitting that white supremacy and racism affect all of us. We need to develop the habit of catching how we have internalized cultural messages about our worth or lack of worth and often act out of those messages without realizing it. We need to develop the habit of catching how we reproduce dominant culture habits of leadership - power hoarding, individualism, one right way. We need to offer ourselves deep compassion and grace if we are dealing with severe trauma related to oppression. We must notice if we are addicted to a culture of critique, where all we know to do is point out what is not working or how others need to change. We need to be able to see how our conditioning gets in our own way and in the way of others. We also need to be able to see and claim our power, our wisdom, our bravery, our intuitive and emotional and intellectual gifts. Knowing ourselves requires vulnerability, authenticity, and a sense of humor. Doing our personal work so that we can show up for racial justice is, ironically, a collective practice. We need to support each other as we work to build on our amazing strengths – our power, our commitment, our kindness, our empathy, our bravery, our keen intelligence, our sense of humor, our ability to connect the dots, our creativity, our critical thinking, our ability to take risks and make mistakes. We also need to support each other as we work to address the effects of trauma and the dis-ease associated with white supremacy and racism. We do this by calling each other in rather than out. We do this by holding the contradiction that we are both very different from each other as a result of our lived experience and we are also interdependent as a growing community seeking and working for justice. We do this by taking responsibility for ourselves and how we show up to facilitate movement building. See A Word About Healing below for more on healing from the trauma of white supremacy culture. |

|

I have spent the past two and a half years moving through a personal situation that has offered the opportunity to face some of my deepest fears, which in turn has shown a spotlight on some of my deepest conditioning. I can get very discouraged when I see old and worn and familiar patterns return again and again even as I am working hard to get free from my often brutal and harmful conditioned thoughts. I have found this story about metamorphosis particularly helpful as I consider how often my conditioned thoughts have to die before new ways of thinking can emerge and take hold. This is an excerpt from Leon Vanderpol's book A Shift in Being (p. 57): Metamorphosis for a caterpillar is a process of death and emergence, not morphing. Wrapped in its cocoon, its body decays and disintegrates into a blob of primordial goo, a nutrient-rich stew of death cells mixed with some bits and pieces of the caterpillar's innards. Then one day something remarkable happens: in the midst of the puddle of decaying ooze, a new cell pops up - ping! These cells have been called 'imaginal cells' because they are imagining what is possible. The immune system of the dying caterpillar, taking the imaginal cell to be some sort of enemy form, attacks and kills it. Another imaginal cell then pops up - ping! - and the immune system again trounces it. Soon a number of imaginal cells pop up - ping! ping! ping! - and the immune system, although it's beginning to fail from the stress of death, continues to fight. In time, however, the imaginal cells pop up faster and in greater numbers than the fading immune system can kill them off. And then, because the imaginal cells are encoded with the program to create a butterfly, they start joining together to form cell clusters: clusters of wing cells, antenna cells, digestive tract cells and others take form. The cell clusters eventually form together and the transformation is complete - the butterfly emerges as an altogether new entity. |

Take a look at this video if you want to see the entire metamorphosis process.

|

work on all three levels

Artwork by Leahjo Carnine

Artwork by Leahjo Carnine

dRworks offered one framework to understand racism based on how it shows up on three levels: personal/interpersonal (how we are with ourselves and each other), institutional (policies, procedures, practices), and cultural (beliefs, values, norms). Liberation shows up on all three as well. This principle suggests that working for racial justice means we need to work on each of the three levels. If our organization or community offers expertise and skills in two of the three, we can intentionally partner with organizations and communities working on the other. For example, an organizing initiative focused on teachers in a mid-size southern city is offering yoga classes for their members, led by yoga teachers committed to tying their practice to the vision of building a strong public education.

We must avoid the tendency to pit one level against another, to place such a strong focus on one aspect of liberation that we ignore or even disdain the others. Many of us are familiar with the individual committed to fighting for justice in the world while sacrificing relationships with friends or family. Many of us are familiar with social justice organizations that exploit the people doing the work of the organization. Similarly, we likely know individuals who spend so much time engaged in personal reflection that they become lost to the movement, or organizations who focus on personal work without tying that work to movement building.

An example of work on all three levels is an emerging national network of racial justice activism and activists. The network is grounding leadership in a somatics practice designed to support transformational change rooted in the belief that we benefit from understanding how trauma impacts us emotionally, physically, intellectually, and spiritually. The work of understanding our own personal relationship to trauma is done as a collective practice in the service of developing our individual and collective capacity to facilitate the day to day work of movement building.

We must avoid the tendency to pit one level against another, to place such a strong focus on one aspect of liberation that we ignore or even disdain the others. Many of us are familiar with the individual committed to fighting for justice in the world while sacrificing relationships with friends or family. Many of us are familiar with social justice organizations that exploit the people doing the work of the organization. Similarly, we likely know individuals who spend so much time engaged in personal reflection that they become lost to the movement, or organizations who focus on personal work without tying that work to movement building.

An example of work on all three levels is an emerging national network of racial justice activism and activists. The network is grounding leadership in a somatics practice designed to support transformational change rooted in the belief that we benefit from understanding how trauma impacts us emotionally, physically, intellectually, and spiritually. The work of understanding our own personal relationship to trauma is done as a collective practice in the service of developing our individual and collective capacity to facilitate the day to day work of movement building.

|

A WORD ABOUT HEALING White supremacy capitalism is deeply traumatic. All we have to do is look around and see how many of us suffer from some version of PTSD, addiction, alcoholism, depression, suicidal thoughts, homicidal thoughts, mental dis-ease and exhaustion, physical dis-ease and exhaustion. In order to avoid causing further trauma, I am not going to share the statistics here. I will just say that the evidence of massive dis-ease is all around us and you, the person reading this, may be one of those navigating one or more of these dis-eases. Working on all three levels includes acknowledging our need to heal. I have spent the last two and a half years going through one of the hardest transitions of my life. This has required a lot of self-care. And I have noticed how taking care of myself in this white supremacy culture is often offered as one wounded person (me) sitting in an office with another hopefully more healed person (my therapist or designated healer) where an exchange of money is required in order for (my) individual healing to occur. In this culture, we often assume that healing is possible without consideration of the larger context - that we are constantly navigating a world where those in power are inflicting their abusive commitment to profit and power on us. I have come to understand, and many of you already know this, that healing is actually a collective process, a community process, a gathering together of the harmed and wounded in ways that allow us to weep and mourn and honor our suffering as we help each other through it. I take great heart and hope from the growing efforts of wise healers to offer collaborative and collective practices, including somatic practices, that address and honor the deep trauma that white supremacy visits on us physically, emotionally, mentally, and spiritually. More and more of us are understanding the ways in which we hold trauma in our bodies and are turning to each other for help remembering how to breathe, how to move, how to allow emotions to move in and out and through. That said, because white supremacy capitalism likes to devour anything that attempts to transgress it, we are also witness to the cooptation, cultural appropriation, and commodification of healing and wellness. Like anything we do, we must bring intention to our healing. We must ground ourselves and our healing practices in shared values of equity and justice and reparations of historic violence and harm. Some examples of grounded healing that many of us have turned to include Resmaa Menakem's book My Grandmother's Hands. Michelle Johnson, who was one of the founding trainers at dRworks, offers a racial justice practice based in healing (or perhaps a healing practice based in racial justice). Anjali Taneja, Cara Page, and Susan Raffo, in collaboration with other healers, have been tracing the medical industrial complex to inform and shape a vision for collective care and safety and opportunities for transformation. We are witness to healing trauma in the form of Black and Brown land reclamation, Indigenous language retrieval, prison abolition, reparations, cultural practices by and for the people and communities (re)producing their culture. And/or the creation of thoughtful and appropriate cultural practices to meet our needs to be seen and heard in ways that mainstream cultural practices will not and cannot offer. The good news is that we continue to build our collective resiliency and grace and ferocity and patience every day in so many ways. We need and deserve to heal from white supremacy culture. We do this whenever possible with and for each other. |

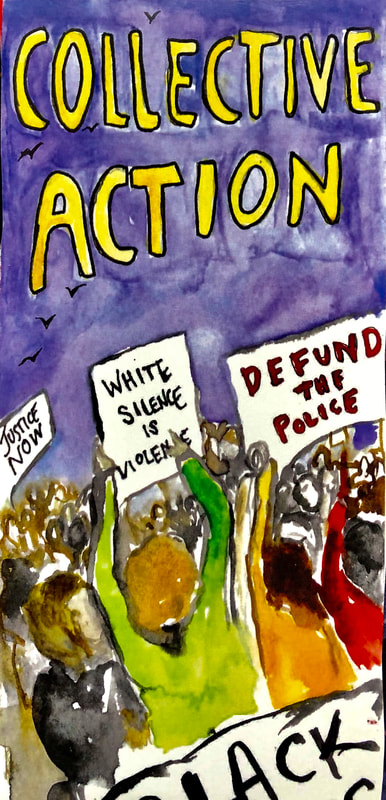

think and act collectively

|

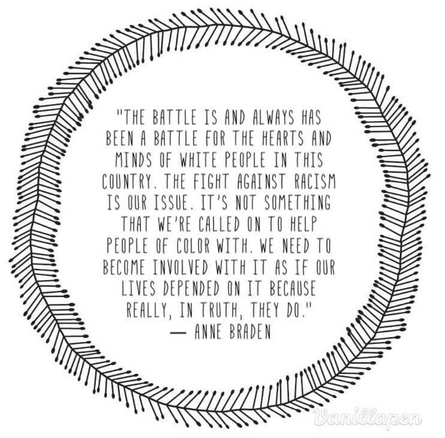

We live in a culture enraptured by the idea of the single hero riding in on a white horse (or an inter-galactic spaceship) to save the day. We are all of us raised by institutions (schools, the media, religious institutions) that reinforce the idea of individual achievement and heroism. The reality is that our history and particularly the history of the arc of social justice is a history of movements. This principle is based on the idea that we save and are saved by each other. By design, this culture insures that we have a very weak collective impulse; the collective impulse that people and communities held originally (Indigenous nations and cultures) or brought with them from other countries and cultures, has been systematically erased in the service of white supremacy, capitalism, racism, and power hoarding. This means that we (may) have to (re)teach each other and ourselves to collaborate and act collectively. We can look for guidance to those people and communities whose resilience has preserved that impulse. Acting collaboratively and collectively means that we build strong and authentic relationships that enable us to act in concert with each other from a place of wisdom gathered collaboratively and collectively. It also means that we learn from our mistakes rather than pretend we never make them. |

|

|

|

In my conversation with healing justice activist Susan Raffo, she talks about the pursuit of happiness as a collective pursuit. The great Solomon Burke illustrates that idea with this wonderful rendition of None of Us Is Free. |

honor and build power in and with the margins

|

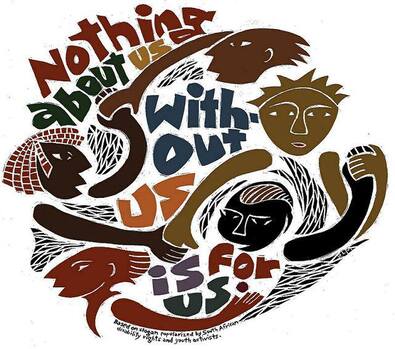

This principle comes to us from the trans community and the writing/thinking of Dean Spade. Spade, a trans activist, writer, and teacher, explains how strong equity goals are best designed when they build the power and agency of those who have been pushed by the mainstream to the outer margins. This principle recognizes that when we frame goals and strategies in ways that benefit those living on the margins, or better yet, when we frame them led by or with those living on the margins, we are framing goals and strategies that benefit all of us, directly and indirectly. One example is curb cuts, which came to us because of those who fought for the Americans with Disabilities Act. Curb cuts are a wheelchair accessible design and they benefit all of us - people pushing baby carriages, people on skateboards or bicycles, people who have trouble stepping up or down a curb. Another example is health benefits; when we fought (or fight) for health coverage for domestic partners (which is and should be a right), that goal and the strategy to reach it still leaves those who are single, trans, queer, unemployed, or living in other than traditional relationships as well as a large range of poor people vulnerable. Crafting and fighting for health care that covers all of us achieves more equity and builds a larger caring community.

|

|

|

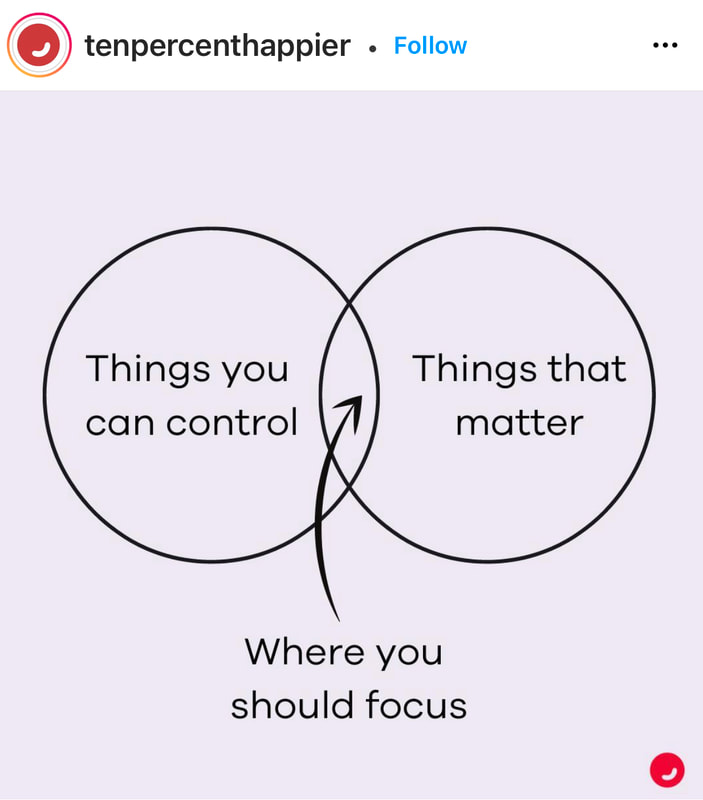

This principle is grounded in the wisdom of experienced and effective community organizers. Organizing mind means that we begin by looking around to see who is with us, who shares our desires and our vision. We then build relationships with those people. So, for example, if we find one other person to work with, then the two of us find another 2 people, then the four of us find another 4 people and so on. Organizing mind is based on the idea of “each one reach one” (thank you Sharon Martinas) in ways that build relationships, community, solidarity, and movements. Organizing mind helps us to focus on who and what is within our reach so we can build a larger group of people with whom to work and play and fight for social justice.

This principle is closely tied to the writing of Stephen Covey (The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, 1992), which is in turn based on the work of Viktor Frankl (Man’s Search for Meaning, 2006). Covey speaks to the importance of focusing on our circle of concern - what we can do something about - which helps us build our individual and collective power. Frankl, a Jewish psychotherapist, was imprisoned in a series of concentration camps during WWII and spent much of his time observing the behavior of his fellow prisoners and the Nazi prison guards. He noticed how some prisoners were more “free” than their guards because of how they used the space between what happened to them and how they chose to respond. Frankl went on to define that space as “freedom.” Our circle of concern includes the wide range of concerns that a person or community has, including everything from a (public) health problem like the Covid pandemic to the threat of losing a job or a loved one (what happens to us). The circle of influence focuses us on those concerns that we can do something about (how we choose to respond). Proactively focusing on our circle of influence magnifies it; as a result our power and effectiveness build. Reactively focusing on concerns that are not within our circle of influence, on what’s not working or on what others can or should be doing, makes us much less effective. It can also encourage us to blame and/or wait for others to change before we act, which leads to a sense of frustration and powerlessness. The connection to organizing mind is that too often we focus our efforts on people who are too far away from us (our circle of concern) rather than on those who are closer who we haven’t yet organized to work with us (our circle of influence). When people complain that “we’re preaching to the choir,” our response is “yes, we need to start organizing the choir.” When people complain about the apathy or disinterest of those we are trying to reach, this is often a sign we are too focused on who is not yet with us and we need to refocus on who is, even if it’s only one or two other people. |

take risks and learn from our mistakes

This culture often teaches us that to make a mistake is to be a mistake. Maurice Mitchell, one of the leaders of Black Lives Matter, makes the point (and he is talking to and about white people here) that his liberation and that of other Black and Brown people has nothing to do with our anxiety. He notes that we will inevitably make mistakes and our anxiety about making mistakes does not serve us or the movement. Failure to take risks because we are afraid of failure or our own vulnerability does not serve us or others. Denying that we made a mistake also does not serve us or others. Failure to learn from our mistakes is the only real mistake we can make.

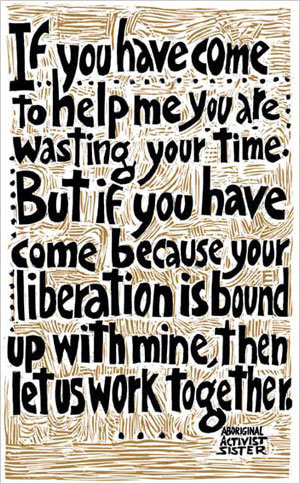

That said, this principle also acknowledges that BIPOC people and communities take risks every day; to live in a white supremacy culture is a risk. This is another both/and situation, where the invitation is to notice and evaluate the risk that is being taken and to take risks thoughtfully with consideration of the consequences. Often the risks white people take have dire consequences for BIPOC people and communities if those risks are taken as individualistic attempts to "fix" or "save" or "set straight." Often white people fail to take any risk in fear of doing it "wrong" or suffering consequences that we can more than afford. Often BIPOC people and communities are expected to take risks and deal with the fallout while white people and communities commiserate or express horror or sadness at the consequences. So this principle is meant to invite us to challenge the white supremacy conditioning that comes from any internalized sense that we have a right to be comfortable or a fear of conflict or perfectionism or one right way thinking. It is beyond time for those of us who are white to collectively speak out and up in service to racial justice.

That said, this principle also acknowledges that BIPOC people and communities take risks every day; to live in a white supremacy culture is a risk. This is another both/and situation, where the invitation is to notice and evaluate the risk that is being taken and to take risks thoughtfully with consideration of the consequences. Often the risks white people take have dire consequences for BIPOC people and communities if those risks are taken as individualistic attempts to "fix" or "save" or "set straight." Often white people fail to take any risk in fear of doing it "wrong" or suffering consequences that we can more than afford. Often BIPOC people and communities are expected to take risks and deal with the fallout while white people and communities commiserate or express horror or sadness at the consequences. So this principle is meant to invite us to challenge the white supremacy conditioning that comes from any internalized sense that we have a right to be comfortable or a fear of conflict or perfectionism or one right way thinking. It is beyond time for those of us who are white to collectively speak out and up in service to racial justice.

set explicit goals - boldly and in context

We all know how easy it is to “talk the talk” – and the talk of racial justice is deeply compelling. This principle asks us to tie the talk of social justice to explicit goals so that we, and our people and communities, have a clear sense of what social justice looks like up close and personal.

Often when people in communities or institutions make a racial equity commitment, they have little to no idea of what that commitment means in terms of their role, their job, or their responsibility. For example, my colleagues and I often work in school settings where the administration has sponsored extensive training to support teachers and staff to get on the same page about what racism is and how it operates, which is a crucial first step. However it often stops there, so while people in the school know what to say, they don't actually understand what they are supposed to do to live into the equity commitment. Working collectively to establish explicit racial equity goals within each person's sphere of influence is critically important. Those leading the change must build a team that can help people identify what racial justice looks like in their sphere of influence, whether it is working for a policy goal to embed equity into the curriculum or an internal organizational goal to insure clear communication across language and cultural differences.

Finally, it helps to understand that once we have set a clear goal and then move towards it, the very practice of working towards the goal will surface new information that will change the goal and broaden our understanding of what is needed. So setting explicit racial equity goals is a dynamic process and our goals are going to shift and broaden and clarify with time and experience.

Often when people in communities or institutions make a racial equity commitment, they have little to no idea of what that commitment means in terms of their role, their job, or their responsibility. For example, my colleagues and I often work in school settings where the administration has sponsored extensive training to support teachers and staff to get on the same page about what racism is and how it operates, which is a crucial first step. However it often stops there, so while people in the school know what to say, they don't actually understand what they are supposed to do to live into the equity commitment. Working collectively to establish explicit racial equity goals within each person's sphere of influence is critically important. Those leading the change must build a team that can help people identify what racial justice looks like in their sphere of influence, whether it is working for a policy goal to embed equity into the curriculum or an internal organizational goal to insure clear communication across language and cultural differences.

Finally, it helps to understand that once we have set a clear goal and then move towards it, the very practice of working towards the goal will surface new information that will change the goal and broaden our understanding of what is needed. So setting explicit racial equity goals is a dynamic process and our goals are going to shift and broaden and clarify with time and experience.

|

White supremacy thrives in a culture of fear. In the U.S., we are constantly navigating a fear based culture. We have a mainstream political party whose primary messaging is fear-based. Fear shuts down our ability to be creative, compassionate, and brave; fear also divides us and pits us against each other. Notice when fear shows up, name it, and seek ways to feel it, address it, and look for ways to build connection and relationship. This principle does not suggest that choosing love is easy. There is a reason we have come up with the term "tough love." Sometimes love means setting boundaries, saying no, calling people (including ourselves) to do better. Even so, we are best served when we ground our actions in a desire for connection and learn to ask ourselves: what would build connection here? Relationship? Love? Even if and when we're asking on our own behalf - what would help me build connection to myself? to love myself? We seek connection not just with ourselves and with each other. We also seek connection with the land; grounding ourselves in where we and our people come from, grounding ourselves in connection to the trees, the water, the air, the sun, the rain, the salamanders and the songbirds ... This grounding restores and reflects the deep respect that we must hold if we are to survive and thrive on this Mother Earth. |

Power without love is reckless and abusive, and love without power is sentimental and anemic. Power at its best is love implementing the demands of justice, and justice at its best is power correcting everything that stands against love. Martin Luther King Jr. |

We must love ourselves. We must encourage love - love that is radical, love that digs deep. Love that asks the hard questions, that is ready to listen to the whole story and keep loving anyway. Love for the survivors, love for the perpetrators, love for the survivors who have perpetrated and the perpetrators who have survived. Love for the community that has failed us all. We live in poison. The planet is dying. We can choose to consume each other, or we can choose love. Even in the midst of despair, there is always a choice. I hope we choose love.

|

Author of I Hope We Choose Love, writes (pp. 101-104) :

We must reject despair and embrace healing, slow and imperfect though it may be, and turn instead to love - love strong enough to live without faith. I am trying to embrace my own healing. I am trying to love my own painful, wounded life. As adrienne maree brown suggests, I am trying to embrace growth and constant transformation, like a flower growing in poisonous radiation. I am trying to let love emerge from my traumatized body. She then goes on to offer a number of concrete steps toward "building this love-based justice," including:

For a more detailed description of these steps, read her wonderful and mind-blowing book. |

and ...

These racial equity principles, like the characteristics, is a tool, not the tool, for trying to understand how we can ground ourselves in racial equity practice. Here are some additional resources.

Mariam Kaba's beautiful website TransformHarm, designed by Lu Design Studio. The website welcomes us with this language: TransformHarm.org is a resource hub about ending violence. We are not an organization. This site offers an introduction to transformative justice. Created by Mariame Kaba and designed by Lu Design Studio, the site includes selected articles, audio-visual resources, curricula, and more. You can use what is here, and submit recommendations to be added to the focus areas listed here. We hope you will use these materials to foster your own education and also share them with your communities to build something new. Only together can we transform our relationships to each other and society. We hope that this site helps in this effort.

|

Claudia Horwitz invites us to invest in the inner skills to cross boundaries, break through fear and bias, and repattern our behavior so that lines of difference do not become fault lines. She explains that by being mindful while stretching ourselves, what is difficult can become generative. From here we can be seen and heard for who we are, connect authentically across boundaries, build relationships of solidarity, and move together towards justice.

|

|

|

White Supremacy Culture | Offered by Tema Okun

first published 2021 | last update 8.2023 |