This page explores our cultural assumption that Individualism is our cultural story - that we make it on our own (or should), without help, while pulling ourselves up by our own bootstraps. Our cultural attachment to individualism leads to a toxic denial of our essential interdependence and the reality that we are all in this, literally, together.

The invitation on this and every page is to investigate how these characteristics and qualities lead to disconnection (from each other, ourselves, and all living things) and how the antidotes can support us to reconnect. If you read these characteristics and qualities as blaming or shaming, perhaps they are particularly alive for you. If you find yourself becoming defensive as you read them, lean into the gift of defensiveness and ask yourself what you are defending. These pages and these characteristics are meant to help us see our culture so that we can transgress and transform and build culture that truly supports us individually and collectively. Breathe into that intention if you can.

The invitation on this and every page is to investigate how these characteristics and qualities lead to disconnection (from each other, ourselves, and all living things) and how the antidotes can support us to reconnect. If you read these characteristics and qualities as blaming or shaming, perhaps they are particularly alive for you. If you find yourself becoming defensive as you read them, lean into the gift of defensiveness and ask yourself what you are defending. These pages and these characteristics are meant to help us see our culture so that we can transgress and transform and build culture that truly supports us individually and collectively. Breathe into that intention if you can.

|

Individualism shows up as:

|

|

I'm the only one shows up as:

|

|

Antidotes to individualism and I'm the only one include:

|

|

Reni Eddo-Lodge talks about Why I'm No Longer Talking to White People about Race - a concise explanation of the frustration associated with white people who defend against or deflect the idea that we are complicit with racism.

|

Robin DiAngelo talks about the ways in which white people defend against or deflect the idea that we are conditioned into racism - all based on the notion of individualism.

|

|

I attended high school in a small Southern college town during the period of federally mandated desegregation in the mid 1960s. Chapel Hill’s approach to “integrating” its school system was to close the historically white and Black schools and transfer the students from both schools into a newly constructed building on the edge of town. This new school kept the name of the white school, Chapel Hill High, the name of the white school teams and most of the other identifiers of the white school. The principal of the white school kept her position; Lincoln’s Black principal was hired as the vice-principal. In an oral history taken years later, one Black student recalls walking down the halls and literally seeing the trophies from Lincoln High, which included those of a decades long undefeated football team, stuffed in the trash.

All of the white teachers moved into the “integrated” school, while the jobs of most of the Black teachers were terminated in a devastating mimicry of what was happening across the South, as school boards and administrators fired over 38,000 Black principals and teachers region wide. Black students at Chapel Hill High were unhappy, angry, and upset at this erasure of their Lincoln High school legacy and experience. They organized and staged sit-ins. Black and white students together organized a “race council,” a structured time for us to meet and talk about what was happening. One evening I hosted the race council at my house. We met in our basement, a sort of recreation room popular in suburban homes of that period. I have a strong memory of “talking” with a young man named Sylvester. He was shouting at me “you’re racist!” I was shouting back, “No, I’m not!” “Yes, you are!” “No, I’m not!” Our “conversation” proceeded in this manner until the moment came when I told him I had to fetch the refreshments. Upstairs, my mother was preparing the drinks and cookies. She turned to me and said, “Get a grip. You’re a white girl, you grew up in a racist country, you’re racist. Deal with it.” I have no memory of what happened next. I do not know if I went downstairs and admitted to Sylvester that I was, according to my mother, indeed a racist. I do know that in that instant, all the energy I had been using to deny my racism turned inward. I began to consider all the ways in which I might be racist. Thanks to this initial push from Sylvester and my mother, I’ve been considering this in one form or another ever since. |

|

Artwork by Tema Okun

sitting on (the) edge |

I am courting grief like a worried bride,

mourning a child not yet seen. I am the great grand-daughter of brides lost, old women swept under worn tables like crumbs of burnt toast. A world weeps for these women or should. Instead, you, the careless, forget; or you, the contented, refuse to see spotted hands, heavy hips, backs and hearts, splintered shards that cut us up and through. Our pain is my question and my answer. I kiss the insults, suture the lacerations I place the bandage just so. I want repair without knowing what waits for me. I am afraid of falling, afraid of flying, afraid of lingering, too long, like my mother, Any minute now, perhaps in another five or so, I will push off. Tema Okun |

|

In the mid-1980s, I was hired to work at the Carolina Community Project, newly formed to support community organizing in the large urban area of Charlotte, North Carolina. The organization and its mission had been conceived by long-time white organizer Si Kahn, who raised the money to hire a staff and get the organization off the ground. He chose Cathy Howell, another experienced white organizer, to lead the staff. She then set about to build a multi-skilled, multi-racial staff to develop the vision, mission, and work of the organization. I was lucky enough to be the last hire, brought on not because of my organizing experience - I didn’t have any - but for my graphic design skills, my interest in fundraising and, I suppose, my track record for working hard at whatever task I was given.

This would be my first experience working with a truly multi-racial staff. While I had worked with BIPOC people before, they had almost always been confined to administrative roles. I had yet to work with a Black or Brown person holding more or even equal authority and power as me. I was at the time a typically dutiful liberal. My naïve enthusiasm about working with a staff that was half African-American and half white made me feel good about myself and the open-minded person I clearly saw myself to be. At our first staff retreat, we spent several days getting to know each other as we grappled with the work ahead of us. I assumed, in my satisfied ignorance, that everyone was as happy to be working in this biracial mix as I was. Sometime during the retreat, Kamau, one of my new colleagues, made an off-hand remark about how hard it had been for him to decide to join the staff. Kamau was, and is, a deeply experienced community organizer, born and raised in the 50s and 60s in a rural South Carolina power structure hostile to Black communities and people both economically and spiritually. He had been unjustly imprisoned for many years; prison was one of the places where he completed his high school education, became deeply committed to social justice, and developed his organizing skills. I turned to him, my young white liberal mind confused about why joining this clearly stellar staff would be hard for him. “Why do you say that, Kamau?” I asked. “Well,” he said patiently, “now I have to explain to my friends back home why I’m working for a white organization.” This was one of my first lessons in the differences between us – me, a young, white, liberal, do-gooding woman, whose only frame of reference was the "nobility" of working across lines of race and Kamau, whose lived experience let him know the dangers of working with white people, no matter how well intended. I had never, ever, not once, considered that Kamau, or others like him, might pay a price for working with me or someone like me. I had never, ever, not once, considered that a BIPOC person choosing to work within a white-led organization might actually face a whole set of challenges that I had yet to understand. This was the first time I realized that the racialized other who I thought of with such paternalistic fondness might not want to be like me or even with me. I would spend the rest of my life learning and re-learning this. I am both sorry for and grateful to my many teachers. |

|

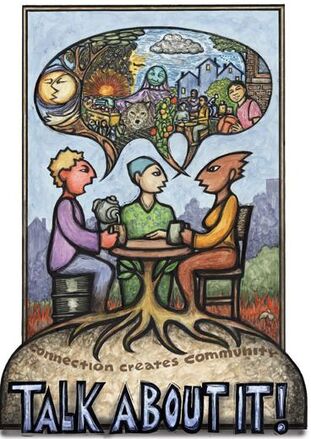

Artwork by Ricardo Levins Morales.

|

antidote

think & act collectivelyWe live in a culture enraptured by the idea of the single hero riding in on a white horse (or a inter-galactic spaceship) to save the day. We are all of us raised by institutions (schools, the media, religious institutions) that reinforce the idea of individual achievement and heroism. The reality is that our history and particularly the history of the arc of social justice is a history of movements. This principle is based on the idea that we save and are saved by each other. By design, this culture works to erase our collective impulse. Concern for and honoring the collective that people and communities held originally (Indigenous nations and cultures) or brought with them from other countries and cultures has been systematically erased in the service of racism. This means that we have to teach each other to collaborate and act collectively. We can look for guidance to those people and communities whose resilience has preserved that impulse. Acting collaboratively and collectively means that we build strong and authentic relationships that enable us to act in concert with each other from a place of wisdom collaboratively and collectively gathered. It also means that we learn from our mistakes rather than pretend we never make them. |

|

I walk quickly past the three mothers. I turn onto the path that leads me to the wise woman. As soon as I arrive I announce, “I am so broken. I can’t do this. I can’t do it.”

My yearning for a connection lost so many years, decades, generations ago is breaking me. “Come,” she says. And she turns to the people. At her cue, they begin to wail with and for me. And then they stop. Because they are not essentially sad. They are joyful. They wail in solidarity, not from actual pain. The wise woman and I sit. She invites me to snuggle with her, to put my head against her shoulder and rest. I do. The wise woman calls the man who started the trouble. He arrives, shapeshifting at the start, finally settling into his now familiar form. He sits on the ground, cross-legged facing us. His brothers stand in a wide line behind him, intimidating. This will not be an easy healing. Wise woman looks him in the eyes. “Why are you doing this?” she asks. She notices, and I do too, the desperation as he drops his gaze. He realizes we see it and his body stiffens with suspicion and hatred. “Why,” she asks again, “when you couldn’t fly, did you pull all the people down?” He doesn’t speak. They sit in silence for a long time, with the drums beating in the background. The people sit off to the side, waiting and watching. Finally he says, “They told me I had to do it -- if we were going to survive on land, we had to be on land.” “Why did you do it?” she asks one more time. He explains that cooperating meant status, a new kind of power, different from that of flying. I sit to the side now, listening. The wise woman asks if he would rather be on land or fly. She asks one of the people to take him to fly so he can remember before he answers. As he is escorted back down to the ground, I realize my time is up. This visit is over. I rise and kiss wise woman on the lips. I turn and bow to the man who started the trouble. I leave. Once home, I am struck by how brave the three mothers and many of the others have been, how brave and resilient. I’m sure some flew in secret and some remembered about the flying even if they couldn’t remember how to fly and some just tried to keep a spark for flying alive. I am very grateful for this yearning, this gift from the ancestors. |

My uncle Jack Griffin, who both knew how to fly and died in a plane accident before I was born.

|

|

White Supremacy Culture | Offered by Tema Okun

first published 2021 | last update 8.2023 |