This page explores our cultural dis-ease with truth telling, particularly when we are speaking truth to power. White supremacy culture encourages a habit of denying and defending any speaking to or about it. White supremacy culture encourages a habit of silence about things that matter and, as the collective of artists fighting the AIDS epidemic so wisely and succinctly said, silence = death.

The invitation on this and every page is to investigate how these characteristics and qualities lead to disconnection (from each other, ourselves, and all living things) and how the antidotes can support us to reconnect. If you read these characteristics and qualities as blaming or shaming, perhaps they are particularly alive for you. If you find yourself becoming defensive as you read them, lean into the gift of defensiveness and ask yourself what you are defending. These pages and these characteristics are meant to help us see our culture so that we can transgress and transform and build culture that truly supports us individually and collectively. Breathe into that intention if you can.

The invitation on this and every page is to investigate how these characteristics and qualities lead to disconnection (from each other, ourselves, and all living things) and how the antidotes can support us to reconnect. If you read these characteristics and qualities as blaming or shaming, perhaps they are particularly alive for you. If you find yourself becoming defensive as you read them, lean into the gift of defensiveness and ask yourself what you are defending. These pages and these characteristics are meant to help us see our culture so that we can transgress and transform and build culture that truly supports us individually and collectively. Breathe into that intention if you can.

|

Defensiveness shows up as:

|

|

Antidotes or suggestions for how to show up in more connecting and healing ways include:

|

"That happens to me too." |

“That happens to me too,” she protests, her voice plaintive and accusing. The tone underneath her words puts me on notice that she is unwilling to seriously consider what I am telling her.

The words come from a white woman, in her 50s or 60s, a do-good school teacher or social worker, hard-working, long suffering, underappreciated. Or at least that is what I am telling myself as my eyes land on her. I don’t actually know anything about her except her race and my guess at an age; the rest is my prejudice painted onto a pinched face framed by shoulder length grey hair atop a slight body leaning against the back of a metal folding chair, legs crossed at the ankles in a pantomime of indifference. Her chair is one of 25 placed in a loose circle, each chair holding another white body, faces all looking my way, curious, a few agitated, and hers, lips set firmly after the explosion of her five words into the middle of the room. I’m standing, breaking the rhythm of seated bodies in this gathering of white people, part of a larger group of community members and activists spending two days attending a racial equity training that I am facilitating with a colleague. The BIPOC people are also meeting in their own circle in a neighboring room. I’m doing what I have done so many times before in so many rooms just like this one. We are gathered in these seats after a morning spent looking closely at the deviousness of white supremacy and racism. We are meeting in separate racial groups to dig deeper, with the hope that these affinity groups will support our ability to speak and share more honestly. This woman is only saying what others are thinking. I know this, even though my body is weary with the truth of it. Racism is so clever and its ability to exclude and exploit and violate Black and Brown bodies eventually finds its way to white bodies too. The tone of her complaint lets me know that she isn’t feeling solidarity, she is feeling unseen. That is, after all, how white supremacy’s zero sum ideology works. Underneath her protest is the conditioned resentment that acknowledging the damage racism does to People and Communities of Color would somehow leave her erased. As her “that happens to me too” gives way to tense silence, I experience what feels like a visitation from god, an electric explosion of cosmic truth in the synapses of my brain. I hear myself say, “yes, and that’s how white supremacy works. Because instead of saying, ‘oh, that happens to me too’ in an opening of mutual recognition, we say ‘but that happens to me too” from a place of resentful defense, rejecting what is essentially an admission of shared experience.” I’m not sure I can do this story justice in writing, because this is a lesson that requires an ability to hear the difference between a “that happens to me too” said with angered defensiveness and the same phrase uttered with weary recognition of shared experience. That difference is evidence of how devious white supremacy is. We’re so desperate to be validated, especially those of us who are brought up to believe that being seen is our birthright, that we fail to notice how the poison of racism inevitably seeps into our lived experience, into our psyches, into our cells. And we find ourselves desperate to claim our own oppression, as if there isn’t enough to go around. And in this way white supremacy claims another victory as it successfully disconnects us from each other across lines of race and from others within our own group too. |

|

Denial shows up as:

|

|

Antidotes include:

|

|

I sat cross-legged on the floor, my back against the seat of the couch, trying to stay anchored as I felt my desire to fight or flee rise from my pelvis into my chest. My breath became shallow and my mind was racing.

The roiling of my insides belied the fairly calm conversation taking place around me. I was at a meeting of our training collaborative. Five of us were seated in a circle – two on the couch, one on a chair, another on the floor next to me; we had gathered as we regularly did to plan. I was the eldest in age and one of two who had founded this team over 10 years ago after Kenneth Jones' untimely and sudden death. Those seated in the circle had joined the group at different points in the last decade; two had joined within the last couple of years. They were raising questions about some of our decision-making processes and suggesting changes to better meet their needs and the needs of the group. And with each suggestion, I felt myself becoming more and more defensive. I had apparently forgotten that one of the characteristics of white supremacy culture in the article I had written decades earlier is this one: leaders perceive calls for change as personal attacks. And this: their defensiveness creates an oppressive culture where people feel they cannot make suggestions or when they do, their suggestions are ignored. The good news is that I had enough sense by this time to just keep breathing. I reminded myself that nobody was actually naming me as the problem although at the same time this was encouragement to consider whether I might be. I noted the speed with which my defensiveness arose, simply because of how threatened my ego felt in the face of a call for change. This was another one of those “ah ha” moments, delivering a level of understanding, and even empathy, for other leaders who might move so quickly to defensiveness without realizing why. I’ve witnessed this behavior play out in one form or another repeatedly, where those feeling accused point their fingers at the accuser who is bravely naming what we are too afraid to know, much less admit. When a Black or Indigenous person claims racism, we blame them for “rocking the boat,” for making us uncomfortable. Or we accuse them of being too sensitive, or not understanding the situation clearly, or anything else that gets us off the hook of actually having to listen to what is being said. So many of us lead or work in organizations devoting too much energy trying to protect existing power structures, because too often, like me, leaders perceive calls for change or the naming of dysfunction as personal attacks. We have internalized that if we are doing it “right,” then no one would have to suggest changes. We have internalized that if we are “good,” then there is no dysfunction. We fail to grasp that our intention often has little to do with our impact. The result, too often, is that much organizational energy is spent trying to make sure that the leaders’ feelings aren’t getting hurt or working around a leader’s defensiveness. That defensiveness creates a culture where people feel they cannot offer ideas because if they do, they risk being ignored, or even worse, punished or isolated. And so it goes. So what can we do about our defensiveness? One thing we can do is create a culture of appreciation, both in how we talk to ourselves and then in our relationships with each other. We can extend this compassion and gratitude to our colleagues, our comrades, our friends and family, particularly when we are in disagreement with each other. In organizational settings, we can recognize that the different roles we play bring different challenges – leading an organization and having to be concerned about the whole is very different than leading a program area or working in the community. So often our conflicts with each other come because we have such different lenses through which we understand the work we are being called to do. Developing the skill to see through the lens of our colleagues and comrades can be extremely helpful in addressing conflict. We can learn to name our power when we have it, and bring transparency about our accountability – including who we are accountable to and how, including who we should be accountable to and how. The dilemma here is how often those of us in social justice organizations are more accountable to funders than to the communities we are organizing and serving, which just replicates problematic dynamics that encourage dependency rather than authentic and mutually reciprocal relationships. We can learn to recognize our own defensiveness when it arises. Defensiveness is well named; it arises because we feel we have to defend ourselves in some way. Defensiveness is a response to fear – fear of losing face, losing power, losing control, losing privilege. Fear of being a mistake (so much worse than making a mistake). So the best defense against defensiveness is learning to name it when it happens. Once recognized, we can then dive in and name what it is we are defending and why. We can look for the cues that let us know we are entering defensiveness. I have come to know that when my breathing gets short and shallow, then I need to pay attention. As soon as I catch that I’ve started to breathe differently, I can usually slow myself down enough to take a pause before I react. Once I realized how defensive I was becoming about the suggested changes to our decision-making processes in the meeting with my colleagues, I was able to remind myself to breathe, relax a little, and listen with a more open mind and heart. I would like to say that my defensiveness melted away; the truth is that I am learning to live with my defensiveness, to notice its presence while trying to show up without acting out of it. Some defenses are easier to let go than others. One of the ways I have learned to let go of defensiveness is to realize that I don’t need to take everything so personally. When I do take things personally, I realize that I’m feeling vulnerable, either about the topic at hand or in my life at the moment. I find it very difficult to stay open-hearted when I am feeling hurt or vulnerable, and so, in those states, I tend to think and feel narrowly and I am more likely to shape feedback as a personal attack. In reality, whatever feedback people offer is information – often extremely valuable information – about who they are and what they feel capable of in that moment, about what they want and need from me. One of many ways to respond when we are challenged is to ask, when we are ready, "tell me more." There is great wisdom in the instruction to "seek to understand" before demanding that we be understood. Another way to respond is to realize that any challenge is really a gift - we are getting information about ourselves, about those we are in relationship with, and about what is really needed. If we can keep our heads and hearts, we can delve deeper and find out what is, in fact, needed, and then we can start to address that. So often we just give up on each other; how much better to be thought enough of to deserve a challenge. And if you're thinking "but what about those times when they are wrong?" or "what about those times when it is a pattern of accusations?" or any of the other "but what about..." queries, this is the complexity of being in relationship with each other. Sometimes we are working out our shit on each other and we tend to work out our shit on the people we're closest to, because that's who is available. I don't have any easy answers; we are continually learning to be with and for each other. I simply think it helps to remember that everything we do and everything the other person is doing has a "good" reason ... even if it doesn't make sense to us in the moment. Acknowledging the good reason can be very helpful in moving through sticky situations, even when there are power imbalances. Just saying. |

We can learn to recognize our own defensiveness when it arises. |

|

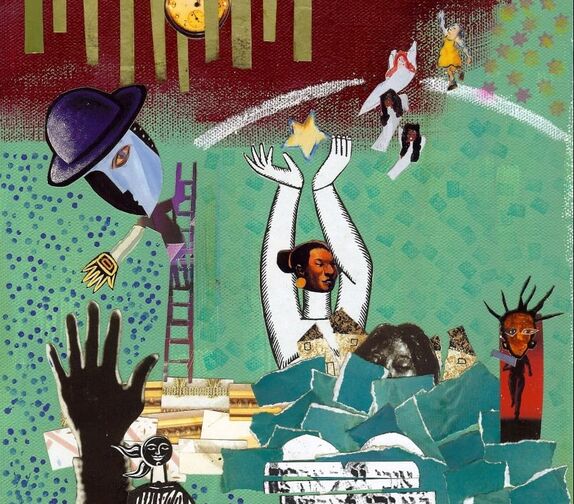

Artwork and poem by Tema Okun

|

reluctant surrender

|

antidote

know yourself

|

Taking action for racial justice requires a level of self-awareness that allows us to be clear about what we are called to do, what we know how to do, and where we need to develop. Another way of thinking about this is that we have a responsibility to know our strengths, our weaknesses, our opportunities for growth, and our challenges. Knowing ourselves means that we can show up more appropriately and effectively to the work, avoid taking on tasks we are not equipped to do well, ask for help when needed, and admit when we don’t know what we’re doing or claim our skills gracefully when we do.

White supremacy and racism affects all of us; we internalize cultural messages about our worth or lack of worth and often act on those without realizing it. We also tend to reproduce dominant culture habits of leadership and power hoarding that encourage defensiveness and denial, individualism, and either/or thinking. We may be dealing with severe trauma related to oppression. We may be addicted to a culture of critique, where all we know to do is point out what is not working or how others need to change. Doing our personal work so that we can show up for racial justice is, ironically, a collective practice. We need to support each other as we work to build on our amazing strengths – our power, our commitment, our kindness, our empathy, our bravery, our keen intelligence, our sense of humor, our ability to connect the dots, our creativity, our critical thinking, our ability to take risks and make mistakes. We also need to support each other as we work to address the effects of trauma and the dis-ease associated with white supremacy and racism. We do this by calling each other in rather than out. We do this by holding a number of contradictions, including that we are both very different as a result of our life experience and we are also interdependent as a growing community seeking and working for justice. We do this by taking responsibility for ourselves and how we show up to facilitate movement building. |

|

White Supremacy Culture | Offered by Tema Okun

first published 2021 | last update 8.2023 |